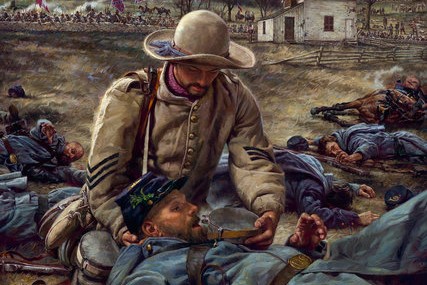

COMPASSION AMIDST DESTRUCTION MADE KIRKLAND THE “ANGEL OF MARYE’S HEIGHTS”

Posted By : manager

Posted : February 25, 2022

By W. Eric Emerson, Ph.D.

On Dec. 13, 1862, Union Maj. Gen. Am-brose E. Burnside issued orders to the Army of the Potomac that would lead to one of the greatest military disasters of the Civil War.

His men had crossed the Rappahannock and fought their way into Fredericksburg on Dec. 11. Two days later, Burnside launched an assault on the forces of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which was arrayed along with a series of hills known as Marye’s Heights.

The key to the Confederate position was a sunken road running along the base of the high ground, where a chest-high stone wall protected Rebel soldiers standing in the lane.

The task for the advancing Union troops was an unenviable one. As they moved down the streets of Fredericksburg before they lay barren fields bisected by canals and covered by artillery and rifle fire for much of their breadth. A ditch pro-vided temporary cover for the columns as they formed for their attack.

The Union assault began around noon. Division after division of Burnside’s men advanced on the stone wall only to be stopped before reaching their objective. Confederate commanders rushed reinforcements to the defenders until four ranks of men were packed into it. The Rebel troops alternately fired in the lane and then quickly moved to the rear ranks to reload.

The effect on the advancing Union “Angel” continued from page 1

formations were devastating. Row after row of advancing soldiers melted before the Confederate front. The fire was so intense that Union survivors could neither advance nor retreat. Instead, they used their dead comrades as shields and prayed for darkness.

The aftermath of the first day’s fight was horrifying. The moans of the wounded floated across the battlefield. As darkness settled over Fredericksburg, the temperature dropped well below freezing. By morning, many of the Union injured in front of the stone wall had died of their injuries or exposure.

Amazingly, some had survived the cold night. Nevertheless, their continued pleading had a profound effect on those nearby.

Among the Confederate defenders behind the wall was Joseph B. Kershaw’s brigade of South Carolinians. One of these was Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland of Company G, 2nd South Carolina Volunteers.

Kirkland was no different from many Confederate soldiers. He was born in Flat Rock Township, Kershaw County, in August 1843, the fifth son of “humble farmers” John and Mary Kirkland. By the battle of Fredericksburg, the 19-year-old sergeant was a veteran of several battles.

For Kirkland, the cries of the wounded Union soldiers were unbearable. He sought out his brigade commander, Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, in a nearby home. There, he asked for permission to aid the Union soldiers. Kershaw relented, but he explained that a cease-fire was not in effect and informed Kirkland that he could not carry a white flag on his mission of mercy. He would therefore be a target for Union soldiers. Nonplused by Kershaw’s admonition, Kirkland quickly collected several canteens, filled them with water, and went over the wall. Union marksmen targeted him almost immediately, believing that he intended to strip their dead comrades.

They quickly realized the nature of his mission when he lifted the head of the nearest union soldier and gave him water. Kirkland left the canteen with the man, covered him with an overcoat, and continued assisting the Union wounded. The firing stopped, and cheers erupted from the Union and Confederate lines as Kirkland made his rounds. He returned time and again with canteens. Finally, he retreated over the wall for a final time to again be with his comrades. There would be other battles for the newly crowned “Angel of Marye’s Heights.”

Kirkland fought at Gettysburg, earning him a promotion to Lieutenant. Soon after that, at the battle of Chickamauga, he was advancing with his company when he was mortally wounded.

Reportedly, his last words were, “Tell my pa I died right.”

His body was recovered and returned home for burial in a small plot near his family’s home.

Kirkland’s notoriety did not die with him at Chickamauga. Following the war, both Union and Confederate veterans hailed him as a hero. His remains were moved to Camden’s Quaker Cemetery in 1909 and placed near the grave of Gen. Kershaw, his former brigade commander.

By 1965 Kirkland’s legacy had grown to the extent that a statue sculpted by the famous artist Felix DeWelden and depicting Kirkland aiding a wounded Union soldier was placed in front of the Stonewall at Fredericksburg.

It stands there today as a monument to man’s compassion amidst the death and destruction of our nation’s most costly war.