How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery

Posted By : manager

Posted : February 23, 2022

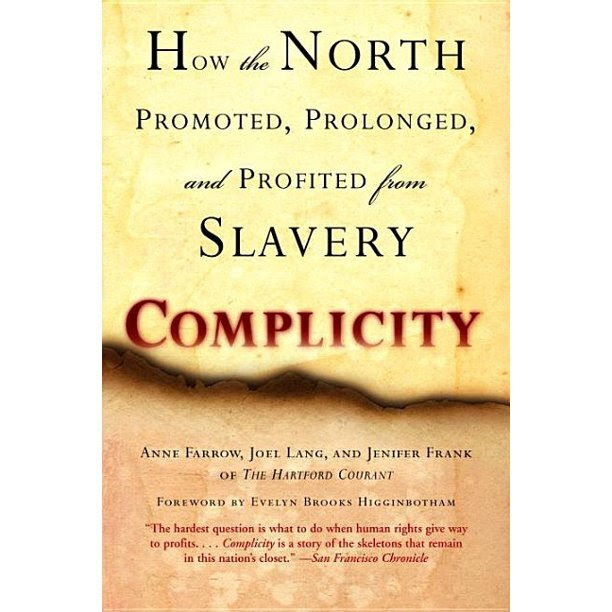

Complicity, How the North Promoted, Prolonged, and Profited from Slavery, by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank of The Hartford Courant – A Comprehensive Review by Gene Kizer, Jr., Part One, Foreword, Preface

A Comprehensive Review of |

COMPLICITY |

How the North Promoted, Prolonged, |

and Profited from Slavery |

by Anne Farrow, Joel Lang, and Jenifer Frank of The Hartford Courant |

Part One: Foreword, Preface |

by Gene Kizer, Jr. |

|

|

IT IS HARD TO BELIEVE this 2005 book was written by journalists in this day and age when so many of them are politicized race-obsessed frauds, but it was; and regardless of its shortcomings, it is a good book and tribute to The Hartford Courant and the authors. Complicity,1 when it first came out, was ignored by the New York Times, which prefers pretend history like the 1619 Project with its primary theme that the American Revolution was fought because the Brits were about to abolish slavery. There is not a shred of evidence of that, not a letter, article, speech or statement by anybody. Nothing. But, then, truth and honor are not the standards of the New York Times. The inside front cover of Complicity states: Slavery in the South has been documented in volumes ranging from exhaustive histories to bestselling novels. But the North’s profit from—indeed, dependence on—slavery has mostly been a shameful and well-kept secret . . . until now. In this starting and superbly researched new book, three veteran New England journalists demythologize the region of America known for tolerance and liberation, revealing a place where thousands of people were held in bondage and slavery was both an economic dynamo and a necessary way of life. One reason for Complicity’s veracity is its extensive use of primary sources rather than the politicized drivel that comes out of most of academia and the news media these days. Complicity shows how the North’s Triangle Trade of “molasses, rum, and slaves” which was run “in some cases by abolitionists” produced great wealth for New England and especially Connecticut. Northerners brought all the slaves here after buying them from other blacks in Africa such as at Bunce Island off the coast of modern Sierra Leone. Slaves were a commodity, a way for Northerners and the British before them to make money, and they did. It is clear from Complicity that much of the infrastructure of the Old North was built on profits from the slave trade. Northerners were slave traders well after it was outlawed by the U.S. Constitution in 1808. W.E.B. DuBois wrote in his famous work, The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870, that Boston, Portland and New York were the slave trading capitals of the planet in 1862, a year into the War Between the States.2 That’s one reason New York City, when the South began seceding, threatened to secede from both New York state and the United States. NYC loved its trade with the South. Shipping cotton was much of that trade as well as financing the Northern slave trade and Southern agriculture. Northerners traded in slaves until Brazil, the last major slave country on earth, outlawed slavery, around 1887. The book, Complicity, started as a special report to The Hartford Courant which was so good “the Connecticut Department of Education sent [it] to every middle school and high school in the state” and it became required reading in many colleges. Complicity should be required reading in every state in the union but instead we get the utterly false 1619 Project, which is pushed hard by the NY Times, the Pulitzer Center and other leftists for whom truth is whatever gives the Democrat Party more power. The Foreword is written by Harvard professor Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham3 who writes that “the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first of the American colonies to give legal recognition to the institution of slavery.” Their recognition preceded Virginia’s.4 She points out the irony: [C]lergy-led Boston, this seventeenth-century ‘city on a hill,’ would soon become a bustling port for the trade in human flesh. Religion proved no match for profits. In Rhode Island, in the Narragansett Bay area, large landholdings used sizable numbers of slaves to provision the mono-crop plantations in the Caribbean with foodstuffs. Such cities as Boston, Salem, Providence, and New London, bustled with activity; outgoing ships were loaded with rum, fish, and dairy products, as slaves, along with molasses and sugar, were unloaded from incoming ships. Up until the American War for Independence, the slave trade was a profitable element of the New England economy.5 Massachusetts “never formally abolished slavery, but rather left it to acts of private manumission . . .”. Private manumission was also how slavery was dying out in the South and would have ended completely without Lincoln’s war that killed a million people and maimed another million. Higginbotham brings out some good points of history but still virtue-signals with regard to the North and its slave traders and business people who got filthy rich because of slavery. They made huge amounts of money manufacturing for the South and shipping Southern cotton. Cotton alone, in 1860, was 60% of U.S. exports. Add to that the other Southern commodities, which all total, were producing the wealth of the United States. Higginbotham celebrates the anti-slavery societies in the North but does not mention that the South had those too, many more than in the North, until violent abolitionists supporting murderers like John Brown caused the South to close ranks for its safety. She does point out Northern racism and admits blacks were not welcome in the North. Northerners wanted blacks to leave the North just as Abraham Lincoln wanted blacks to leave the entire country. See Colonization after Emancipation, Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement, by Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, copyright 2011, first printing 2018). Higginbotham does not point out that racist Northerners didn’t want slavery in the West because they didn’t want blacks anywhere near them in the West. This was Lincoln’s position too. He made it clear in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates that the West was to be reserved for white people from all over the planet. No blacks allowed. Higginbotham does not seem to realize that abolitionists were hated in the North for much of the antebellum period. Abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy was murdered in 1837 at age 34 in Lincoln’s Illinois. Only around 3% of the Northern electorate were abolitionists. None of these virtue-signaling abolitionists had a plan for emancipation that would work such as the Northern states, themselves, had used to end slavery. The Northern states ended slavery like every other nation on earth (except Haiti), with gradual, compensated emancipation. The reason Northerners didn’t suggest a plan that could work is because anti-slavery in the North was political, especially during the elections of 1856 and 1860. It was not a movement for the benefit of the black man. It is better described as “anti-South” rather than anti-slavery. It was political agitation against the South for the purpose of rounding up Northern votes so the North could take over the Federal Government and rule the country. They wanted to continue with their bounties, subsidies and monopolies for Northern businesses, and high tariffs that took money out of the South and deposited it into Northern pockets. Southerners were paying 85% of the taxes but 75% of the tax money was being spent in the North. Despite plans for compensated emancipation in place in some Northern states, six slave state still fought for the North in the War Between the States. West Virginia came into the Union as a slave state during the war, ironically, just weeks after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. The Emancipation Proclamation specifically exempted the Union slave states. Three Northern slave states still had slavery months after the war ended. It took the second Thirteenth Amendment (remember, the first Thirteenth Amendment was the Corwin Amendment that left black people in slavery forever where slavery already existed — it was supported strongly by Abraham Lincoln and ratified by five Northern states including Lincoln’s Illinois before the war made it moot). The special report “Complicity,” that led to the book, came about after The Hartford Courant published a story: “Aetna ‘Regrets’ Insuring Slaves”. The Courant’s journalists started wondering if the Courant, itself, had been complicit in slavery and they found out it had, that it had published ads for the sale of slaves and the capture of runaway slaves. They wanted to find a slave whom Aetna had insured and write about his or her life. What they discovered shocked them to their cores. They thought slavery was a Southern evil, that Northerners were the good guys in the war because they had the Underground Railroad and Harriet Beecher Stowe. But now: [I]t was becoming clear that Connecticut’s role in slavery was not only huge, it was key to the success of the entire institution. . . . We were now looking at nothing less than an altered reality.6 The more they looked for their ties to slavery, the more “unshakable” was the proof they found: It became obvious that our economic links to slavery were deeply entwined with our religious, political, and educational institutions. Slavery was part of the social contract in Connecticut. It was in the air we breathed.7 They found out there were 5,000 African slaves in Connecticut in 1775 and “in 1790 most prosperous merchants in Connecticut owned at least one slave.” So did half of the ministers.8 |